Speed up time to market of innovations as well as new projects

We now know that project portfolios can be executed >25% faster. All relevant knowledge, experience and examples are available. We will be happy to share them with you.[1]

The leap in productivity that can be achieved is desperately needed to bring the energy transition, climate adaptation and the Replacement & Renovation task in European infrastructure forward. However, the productivity leap in project execution at our disposal will be of no avail if we do not also guarantee the time to market of projects. Managers of infrastructure such as Liander, Stedin, Nexis and Rijkswaterstaat in the Netherlands have a challenge in this regard.

Infrastructure managers share this challenge with managers in enterprises. Many worry that promising ideas got stuck in the innovation funnel for too long. Every day of delay means a cost in lost opportunity, not to mention the social costs. The Ukraine crisis adds urgency to the energy transition and makes us face the fact that we should not waste the limited capacity of the infrastructure sector. Do we console ourselves with the thought that shared sorrow is a sorrow halved? Or are we going to work with techniques to speed up the time to market of innovative ideas and new projects?

Good ideas are often a leap into the dark

Naturally, almost everyone likes to think out ideas on a blank sheet. We are not bound by rules and tried and tested methods now, it seems. After all, we are working on something new? Nothing step by step or incremental. We can be disruptive unhindered. Keynotes and policy plans have rammed in the message: innovation is a must! And we like to understand that this way: if something is innovative, it is good.

Unfortunately, this is not as simple as it sometimes seems. What about, for example, the idea of equipping the quay walls that need to be restored in Amsterdam with heat pumps? The relatively warm water in the summer is stored to heat buildings in the winter. Both from a technological and social perspective a highly inspiring idea, but what is its economic added value? Implementing it unhindered is a leap into the dark and could turn out to be a costly disillusionment.

We worked together with an infrastructure owner on the question of how to test innovations for economic added value. In the infrastructure sector, there are ideas for innovations that standardise the control of works of bridges, viaducts and locks – which make operation and management and maintenance easier as well as adaptation to new developments, such as cyber security. However, the application of new techniques entails risks. In the past, the implementation of new techniques has often led to delays and high increases in construction costs. So, the question is: how can we minimize the risks associated with the development of new techniques and increase the chances of success?

Innovation through value creation

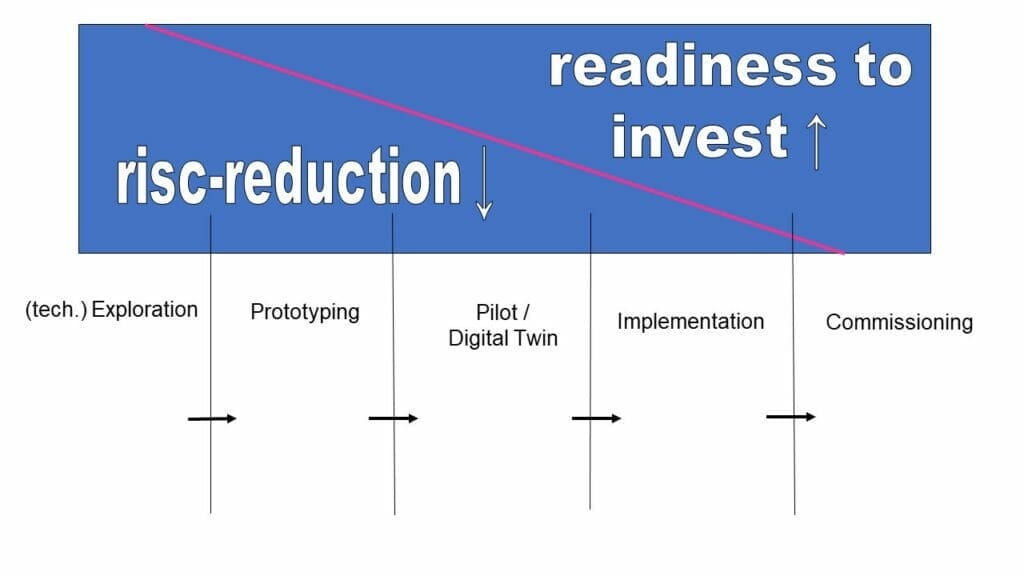

When people hear the word innovation, most think of new techniques. They often completely overlook that innovation is also a process of economic value creation. One-sided attention to technology leads to solutions for which there might be no application. Solutions without added value, that in the worst case can actually drive us to high costs. The figure below shows us why.

The diagram makes it clear that the implementation of a new technique should be preceded by three steps that minimise the risks and increase the chance of success and as a consequence the willingness of infrastructure owners to invest: the (technological) exploration, prototyping and pilots – for example with the help of a digital twin. In the first step, you determine the purpose of use and the potential for quality improvement, safety and cost savings. You will also research alternative solutions and technologies. It is important that when the objectives of one phase have not been achieved, you do not continue. You should now go back to start. But it may also be that you have learned things on the basis of which you cancel the entire project. That may hurt, but the good news is that this saves you from failure at a later stage. After you wasted time and burned money. Be happy, you now have the capacity for new ideas available.

The process of innovation through value creation varies from case to case. But the principles are the same everywhere.

- Phasing. You have to shape the process in steps. Like the steps in figure 1 or alternatives that fit the situation.

- Deliverables. Each step results in deliverables that have been defined and agreed upon in advance, with concrete content and concrete standards. Above we have mentioned a few examples, we can help you with a list of examples to find the ones that suit your situation.

- Go/no-go. After each phase, you need to evaluate and decide whether to go ahead or call off the project.

- Stakeholders need to be identified and involved as early as possible. If you wait until the last, you run the risk that your idea will not catch on and will be rejected. If you involve stakeholders, investors for example, early on, however, you can use their input to improve your idea. Or they might give you an even better idea that fits your competencies and that they cannot develop themselves…

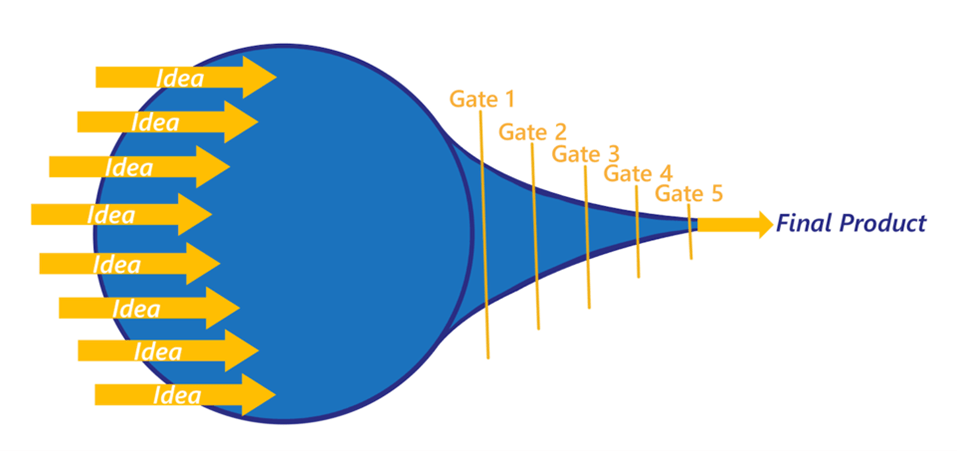

The bottleneck in innovation

Creative people with great imaginations have the ability to see solutions with their mind´s eyes. These people tend to make big leaps from ideas to operationalisation (see figure 1). Their enthusiasm is contagious and soon they will have supporters who find that the idea should be espoused. Technical innovations such as heat pumps in quay walls that surround the beautiful Amsterdam canals and keep people warm in winter appeal to the imagination, but are also associated with risks. The willingness of investors to step in can be gained by reducing the risks step by step. (Parties willing to join if the infrastructure owner pays, that is, is willing to burn taxpayers’ money, are usually plentiful. In Amsterdam, people are aware that stacking ambitions endangers all ambitions. In our next blog, we will show that a clear separation between innovation and operational projects makes it possible to reach even more ambitions.

The bottleneck in innovation management is the collaboration between all stakeholders that are needed to bring the best possible solution to the market in a process that makes optimal use of the input of all parties involved. The image of the bottleneck, to recall the mother of all bottlenecks, makes it clear that identifying the bottleneck is the best possible starting point for the greatest possible productivity improvement. There is no other way to empty the bottle than through the bottle neck – smashing the bottle is a solution that you can only apply once of course, and after that, you will no longer have a bottle. It is always about finding the best possible technique to manage the bottleneck. In the case of the bottleneck, the bottle deflates four times faster if you turn the bottle over and insert a straw almost to the bottom. The technique around the bottleneck in innovation is of course more complicated. Above you have seen the application of the four most important principles. That’s a good start.

It is no coincidence that an image of the bottleneck in innovation management is very similar to a real bottleneck. The image clarifies that in the race to the market, ideas must fall away to free up capacity for the few or one idea that will bring the organisation the greatest possible productivity improvement. In addition, methods are needed to compare the added value of different innovative solutions in order to be able to select the one with the highest added value. We will be happy to discuss with you how this applies to your situation. You can schedule a meeting for this. You can also send us an email.

Our next blog will discuss the solution to a question that multiple readers asked us: how do you divide your organisation’s limited capacity between innovation and operational projects? The answer to this question contributes to further productivity increases and, maybe even more importantly, ensures that technical people, who are difficult to find, choose to work for your organization.

[1] See our previous blogs

Willem de Wit, Menno Graaf, Ian Heptinstall, Hugo van Merrienboer, Emmo Meijer

© 2022 Mobilé 4 flow & innovation